Last Updated on February 14, 2026 by Patrick Camuso, CPA

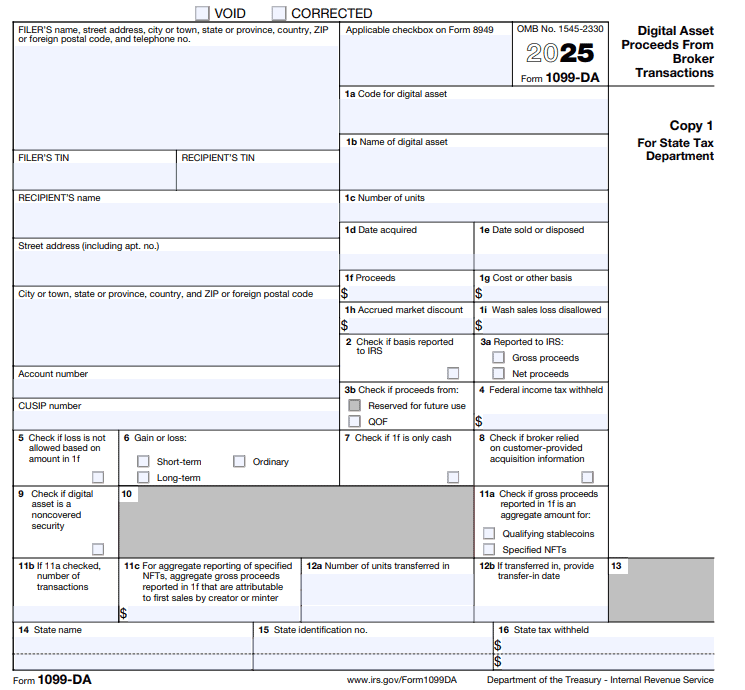

Form 1099-DA introduces standardized, third-party reporting for digital-asset dispositions at scale. That reporting gives the IRS a reliable anchor point for automated matching and discrepancy analysis across tax years, accounts and platforms.

For many taxpayers, the risk introduced by Form 1099-DA is not current-year activity. It is whether historical digital-asset activity, often spanning five, ten, or more years, was ever documented well enough to support accurate reporting once third-party data enters the system.

The IRS has publicly indicated that digital-asset reporting non-compliance remains widespread, often affecting a majority of taxpayers engaging in digital-asset transactions. In practice, that non-compliance is rarely the result of intent. It is structural. Early crypto activity occurred in an environment with no broker reporting, inconsistent records, limited tooling and little practical guidance.

Form 1099-DA does not expose early-year crypto activity directly. It exposes whether early-year activity can be reconciled to modern reporting systems.

That is the risk investors now face.

Why Early-Year Crypto Activity Is Structurally Undocumented

For most long-term digital-asset investors, early activity occurred in a fundamentally different environment than exists today.

For much of the period from crypto’s inception through the early 2020s, digital asset activity occurred in environments without standardized recordkeeping, durable custody continuity, or broker-style reporting, creating structural documentation gaps that persist today. Wallets were self-managed, exchanges came and went and APIs changed or disappeared. Internal ledgers were incomplete or nonexistent.

Tax compliance during that period depended almost entirely on taxpayer-curated records. For many participants, those records were partial, fragmented, or never created at all.

In practice, we routinely see taxpayers with:

- Five to ten years of unaccounted activity

- Assets that moved repeatedly between wallets and platforms

- Early acquisitions with no preserved acquisition documentation

- Multiple exchanges that no longer exist or no longer provide historical exports

This is not bad faith. It is legacy accounting debt.

The IRS has repeatedly stated that digital-asset reporting non-compliance is substantial, often estimated to affect a majority of taxpayers engaging in digital-asset transactions. That assessment aligns with what top practitioners like Camuso CPA see daily, most taxpayers simply did not have the infrastructure to comply accurately when the activity occurred.

Why Form 1099-DA Forces Historical Accounting Before Current-Year Compliance

Form 1099-DA reports dispositions that occur in the current tax year. But cost basis, the element that determines gain or loss, often originates years earlier and is not directly reported on Form 1099-DA.

When a taxpayer disposes of a digital asset in 2025, the tax outcome depends on:

- When the asset was acquired

- How it was acquired

- What was paid for it

- Whether it was transferred, wrapped, bridged, or otherwise modified

- How basis was carried forward across accounts and wallets

Form 1099-DA does not solve those questions. It surfaces them.

A taxpayer cannot “start clean” in 2025. Current-year reporting accuracy depends on whether historical activity was properly accounted for and whether basis can be substantiated today.

IRS matching systems do not pause because accounting is difficult. They compare third-party proceeds data to what appears on Forms 8949 and Schedule D. Where proceeds appear without corresponding, substantiated basis, discrepancies arise.

Form 1099-DA exposes unresolved historical accounting failures that make accurate current-year reporting impossible without historical cost basis reconstruction.

Covered vs. Noncovered Assets Under IRC §6045(g)

Understanding why cost basis is often missing on Form 1099-DA requires understanding the covered-asset framework under IRC §6045(g).

Brokers may generally report basis only for assets they tracked continuously from acquisition through disposition within the same account. That condition is rarely met for early digital-asset activity.

Once custody lineage breaks, through withdrawals, transfers, bridging, wrapping, or assets acquired before basis reporting applied and not tracked from acquisition, the asset is generally treated as noncovered for broker basis reporting purposes.

At that point, §6045(g) does not require and in practice does not permit brokers to report basis they did not track as covered assets, even if the taxpayer later provides documentation.

This is why missing basis on Form 1099-DA is usually structural, not an error. It is the taxpayers responsibility to reconcile this and accurately report it. Most early-year digital-asset positions are not merely noncovered. They are non-reconstructable without full historical accounting across wallets, exchanges, and years.

Why Form 1099-DA Indirectly Surfaces Early-Year Risk

Form 1099-DA does not report early-year transactions. It reports current-year dispositions that originate from historical positions.

From an enforcement perspective, broker-reported proceeds provide an anchor point for discrepancy detection, not a ceiling on what the IRS may examine. The IRS does not need full visibility into historical activity to identify mismatches. It needs only a reliable reference point.

From a taxpayer perspective, this creates two risks:

- False negatives: Activity not reflected on Form 1099-DA may still be reportable. The absence of a form does not eliminate a reporting obligation.

- False positives: Broker-reported proceeds may reflect transactions already reported, offset by basis or losses not visible on the face of the form.

Both risks stem from the same misunderstanding, equating Form 1099-DA with completeness.

The CP2000 Enforcement Timeline and Why Timing Matters

Enforcement under Form 1099-DA will likely begin with automated discrepancy analysis.

The typical sequence is:

- Broker-filed Forms 1099-DA are ingested into IRS systems

- Automated matching compares proceeds to filed returns

- Discrepancies generate CP2000 notices proposing adjustments

- Taxpayers are given limited time to respond, often around 30 days

CP2000 notices are not audits. They are proposed adjustments generated by the Automated Underreporter (AUR) program when matching fails.

Critically, missing basis does not delay this process. Proceeds alone are sufficient to initiate enforcement. When basis is unsubstantiated, the burden shifts to the taxpayer to explain and document the difference.

By the time a CP2000 tax notice arrives, the accounting work required to defend basis should already be done.

Why Multi-Year Cost Basis Reconstruction Is Often Required

Digital-asset cost basis is inherently cumulative. Unlike income items that reset annually, digital assets are held across years, transferred across wallets and platforms, and disposed of incrementally. Early acquisition lots flow forward into later dispositions, meaning current-year tax outcomes are mathematically dependent on historical activity.

For many taxpayers, this creates a sequencing problem since they cannot calculate accurate basis for a single reported disposition without first determining the remaining inventory of units and basis carried forward from prior years.

In practice, this means that current-year reporting often depends on reconstructing the entire transaction history from inception.

Several structural features of digital assets make this unavoidable:

- Lots persist across tax years. Units acquired years earlier may be partially disposed of today, requiring identification of acquisition date, cost, and holding period that predate the reporting year.

- Transfers break visible lineage. Moving assets between wallets, exchanges, or protocols does not reset basis, but it does sever automated tracking unless records are reconstructed manually.

- Partial dispositions require inventory accuracy. Without knowing which units remain after prior disposals, it is impossible to determine which units were sold in the current year under FIFO or specific identification.

- Universal pooling is no longer viable. As taxpayers transition to wallet- or account-level tracking, historical allocations must be established before current-year lot selection can be applied consistently.

- Later activity compounds earlier gaps. DeFi interactions, wrapping, staking, and consolidation events layer complexity on top of already incomplete early records, increasing the dependency on accurate opening balances.

As a result, many taxpayers must reconstruct five, ten, or more years of activity simply to calculate defensible basis for current-year reporting. This is not a function of over-compliance; it is a mechanical consequence of cumulative asset accounting.

The key insight is that basis reconstruction is not backward-looking cleanup, it is forward-looking necessity. Without establishing accurate historical inventory, current-year reporting becomes estimation rather than substantiation, exposing taxpayers to mismatch risk once third-party proceeds data enters the enforcement pipeline.

Why Software Cannot Solve Undocumented History

Tax software is a computational tool. It performs calculations based on the data it is given. It is not a substantiation engine, and it does not create records where none exist.

Most crypto tax software operates on a set of implicit assumptions. It assumes that transaction histories are complete, acquisition data is available, and opening balances accurately reflect prior activity. When those assumptions hold, software can efficiently calculate gain, loss, and holding period. When they do not, software cannot repair the deficit, it can only expose it. Learn about our software agnostic approach to digital asset accoutning featured in AccountingToday.

Software cannot:

- Infer missing acquisition dates or costs

- Reconstruct trades executed on exchanges that no longer exist

- Recreate wallet histories where private keys, addresses, or records are lost

- Repair broken custody lineage caused by transfers, bridges, wrapping, or consolidation events

- Determine which units remain in inventory when prior dispositions were never accurately tracked

In these situations, the output may look precise, but the calculation reflects the limitations of the inputs, not the economic reality of the activity.

This distinction matters in enforcement. The IRS does not evaluate tax positions based on the software used to produce them. It evaluates:

- Records supporting acquisition, disposition, and holding period

- Methodology applied to lot selection and basis allocation

- Internal consistency across years, wallets, and reporting platforms

- Documentation sufficient to substantiate the position under IRC §6001

Software screenshots, exports, or branded reports do not satisfy those requirements on their own. They are tools for organizing information, not evidence that the underlying data is complete or correct. In many cases, software is the first place noncompliance becomes visible. It surfaces gaps, inconsistencies, and missing history that already existed.

Undocumented activity is an accounting problem before it is a software problem. Until the historical record is reconstructed and defensible opening balances are established, no amount of recalculation can convert incomplete history into substantiated compliance.

How Rev. Proc. 2024-28 Accelerates Exposure

Rev. Proc. 2024-28 governs the transition from universal to account-level basis tracking for digital assets.

While the procedure provides limited transition relief, it also narrows flexibility. Allocation discipline is now required. Legacy assumptions become harder to defend over time. Importantly, the procedure does not demand theoretical perfection. It requires defensible allocation based on available records and consistent methodology.

Delay compounds difficulty. The longer reconstruction is postponed, the more exposure accumulates. Learn more about Rev. Proc. 2024-28 here.

Why Waiting for a Notice Makes Outcomes Worse

Reconstructing years of activity under notice deadlines is rarely successful. This accounting process is meticulous and time intensive. Correspondence enforcement rewards preparation, not reaction. Many escalations occur not because positions were wrong, but because responses were incomplete, inconsistent, or disorganized.

Waiting for a notice forfeits control over timing, scope, and narrative. The best course of action is do accurately complete the historical digital asset accounting and cost basis reconstruction now to ensure you’re prepared.

Who Is Most Exposed Under Form 1099-DA

Exposure under Form 1099-DA will not distribute evenly. It will concentrate among taxpayers whose historical activity cannot be reconciled cleanly to standardized broker-reported proceeds.

The highest-risk profiles are defined by data discontinuity, not transaction volume.

Long-Term Holders Exiting Early Positions

Investors who acquired crypto between roughly 2013 and 2021 and are only now liquidating often lack contemporaneous basis records. When these assets are sold through a modern broker, proceeds are reported immediately, while basis may require multi-year reconstruction.

Investors With Significant Balances but No Accounting Trail

Many investors accumulated substantial “paper wealth” without ever performing formal accounting. Under Form 1099-DA, liquidation converts unrealized value into reported proceeds before defensible basis exists.

Founders and Early Participants Liquidating Pre-Custody Assets

Assets acquired through early grants, mining, airdrops, or protocol incentives often predate broker custody. When sold later, they are typically noncovered for basis reporting, leaving taxpayers responsible for reconstructing historical facts.

Multi-Wallet and Multi-Chain Participants

Frequent transfers across wallets, exchanges, and chains break custody lineage. Even when total activity is known, tracing which units were disposed of and which basis applies, becomes difficult.

Taxpayers Using Legacy Pooling or Incorrect Accounting Methods

Investors relying on universal pooling, global FIFO, or retroactive lot selection face elevated risk. These approaches no longer align cleanly with account-level broker reporting and reconciliation expectations under Rev. Proc. 2024-28.

Form 1099-DA penalizes gaps between acquisition, custody, and disposition. Investors with fragmented history face the greatest first-wave exposure, regardless of how active they were.

The Digital Asset Compliance Era

Form 1099-DA marks the operational start of what we refer to at Camuso CPA as the Digital Asset Compliance Era.

Digital assets are no longer evaluated primarily through self-reported narratives or fragmented records. They are now assessed through standardized third-party reporting, automated matching, and cross-system corroboration. This is a structural shift.

Compliance no longer hinges on intent, explanations, or retroactive reconstruction under deadline. It turns on whether reported outcomes can be reconciled to third-party data using defensible methodology and consistent records across accounts, wallets, platforms, and years.

Form 1099-DA tests whether historical activity can be aligned with modern reporting systems.

Taxpayers who recognize that shift and prepare in advance retain control over timing, scope, and outcomes. Those who do not encounter compliance through notices, proposed adjustments, and enforced reconciliation.

The Digital Asset Compliance Era has begun. Compliance is no longer reactive, it must be planned. This is why it’s crucual to work with an experienced Crypto CPA.